What are Kubernetes Pods Anyway?

Recently I saw a tweet from the awesome Amy Codes (I really hope that’s her real name) about Kubernetes Pods:

You know why containers in a pod are always scheduled together? It's cuz they're nested containers.

Mind. Blown.

— Amy Codes (@TheAmyCode) August 21, 2017

While it wasn’t 100% accurate (Containers aren’t really a thing. We’ll get to that in a bit) it did point out the fact that Pods are amazing things. It’s worth taking a look at Pods and containers in general and learn what they actually are.

The Kubernetes documentation on Pods provides the best and most complete explanation of Pods but it’s written in a very general sense and uses a lot of jargon. I do recommend you read it though as it’s a better and more correct explanation than I could write. This post will hopefully be a more down-to-earth compliment.

Containers aren’t Containers

Many folks know this already but Linux “containers” don’t really exist. There is no thing called a “container” in Linux. Containers as everyone knows them are normal processes that are executed using two features of the Linux kernel called namespaces and cgroups. Namespaces allow you to provide a “view” to the process that hides everything outside of those namespaces, thus giving it its own environment to run in. This makes it so processes can’t see or interfere with other processes:

Namespaces include:

- Hostname

- Process IDs

- File System

- Network interfaces

- Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

While I said above that processes running in a namespace can’t interfere with other processes that’s not really true. A process can use all the resources on the physical machine it runs on, thus starving other processes for resources. In order to limit that, Linux has a feature called cgroups. Processes can be run in a cgroup much like a namespace but the cgroup limits the resources that the process can use. These resources include CPU, RAM, block I/O, network I/O etc. CPU is usually limited by milli-cores (a 1000th of a core), and memory is limited by bytes of RAM. The process itself can run as normal but it will only be able to use as much CPU as allowed by the cgroup and will get out-of-memory errors if it exceeds the memory limit set on the cgroup.

There are lots of resources on learning more about namespaces and cgroups that are only a Google search away so I urge you check them out. Here are a couple good ones:

- What even is a container: namespaces and cgroups

- Cgroups, namespaces, and beyond: what are containers made from?

The thing I wanted to point out here was that cgroups and each namespace type are separate features. Some subset of the namespaces listed above could be used or not used at all. You could use only cgroups or some other combination of the two (well, you’re still using namespaces and cgroups just the root ones but whatever). Namespaces and cgroups also work on groups of processes. You have have multiple processes running with a single namespace. That way they can see and interact with each other. Or you could run them in a single cgroup. That way the processes together will be limited to a specific amount of CPU and RAM.

Combinations of Combinations

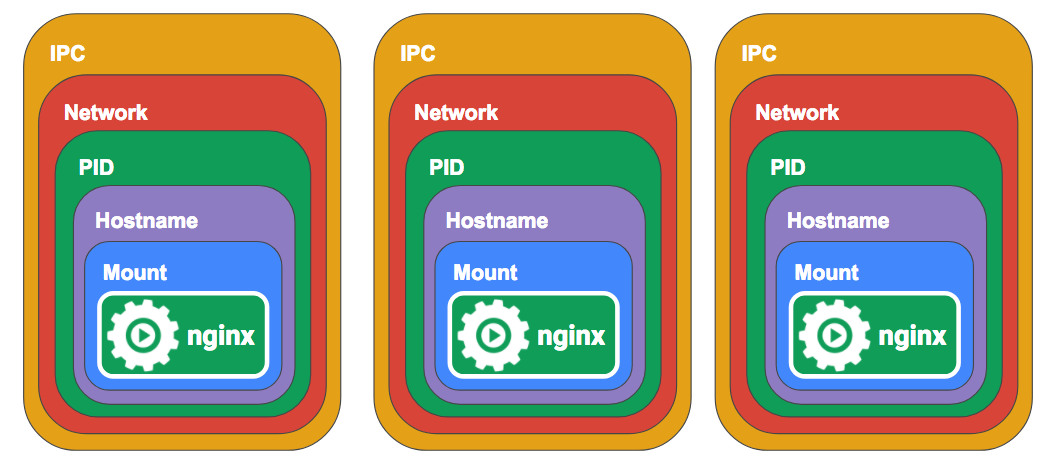

When you run a container with Docker normally, Docker creates namespaces and cgroups for each container so they map one to one. This is how developers normally think of containers.

The containers are essentially stand alone silos, with the exception that they might have a volume or port mapped to the host so they can communicate out.

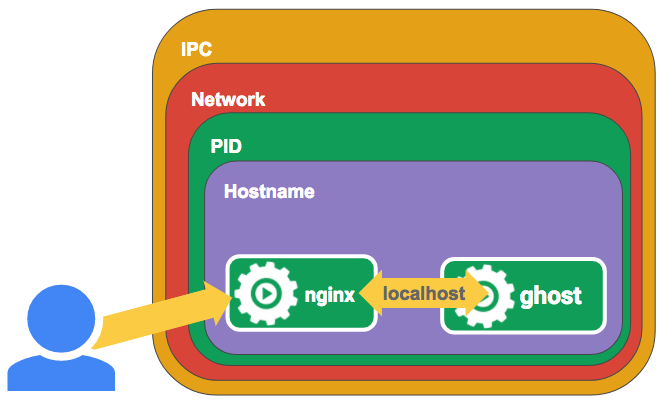

However, with some extra command line arguments, you can combine Docker containers using a single namespace. First let’s create a single container for nginx.

$ cat <<EOF >> nginx.conf

> error_log stderr;

> events { worker_connections 1024; }

> http {

> access_log /dev/stdout combined;

> server {

> listen 80 default_server;

> server_name example.com www.example.com;

> location / {

> proxy_pass http://127.0.0.1:2368;

> }

> }

> }

> EOF

$ docker run -d --name nginx -v `pwd`/nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/nginx.conf -p 8080:80 nginx

Next we’ll run a container with ghost running in it. But this time we’ll add some extra arguments to have it join our nginx container’s namespaces.

docker run -d --name ghost --net=container:nginx --ipc=container:nginx --pid=container:nginx ghost

Now our nginx container can proxy requests directly on localhost to our ghost

container. If you access http://localhost:8080/ you should be able to see

ghost running through an nginx proxy. These commands create a set of containers

running in a single set of namespaces. These namespaces allow the Docker

containers to discover and communicate with each other.

Pods are Containers (sort of)

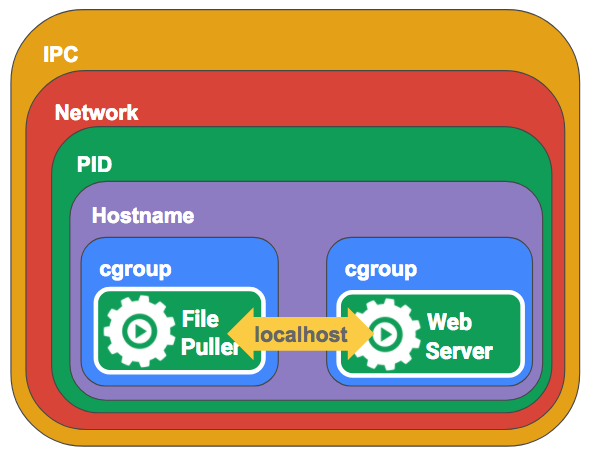

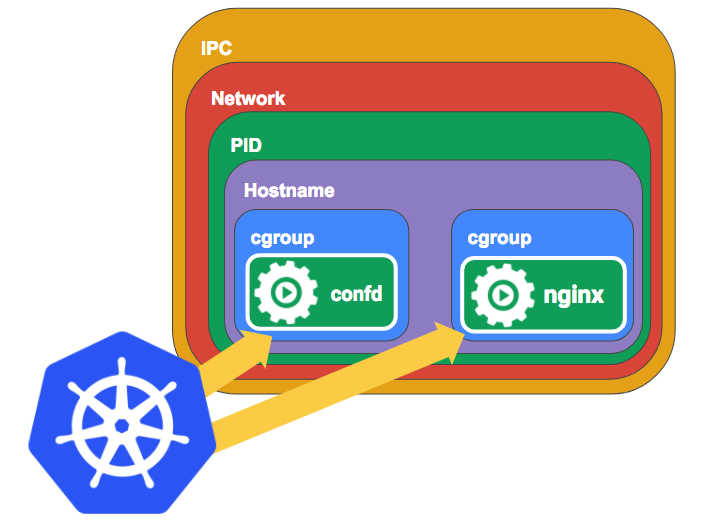

Now that we’ve seen that you can combine namespaces and cgroups with multiple processes, we can see that that’s exactly what Kubernetes Pods are. Pods allow you to specify the containers that you want to run and Kubernetes automates setting up the namespaces and cgroups in the right way. It’s a little more complicated than that, because Kubernetes doesn’t use Docker networking (it uses CNI) but you get the idea.

Once we have our containers set up this way, each process “feels” like it’s running on the same machine. They can talk to each other on localhost, they can use shared volumes. They can even use IPC or send each other signals like HUP or TERM (With shared PID namespaces in Kubernetes 1.7, Docker >=1.13).

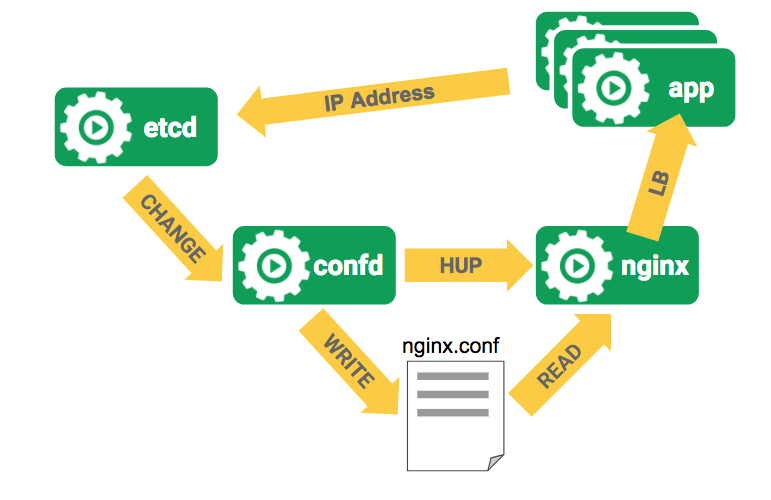

Let’s imagine now you want to run nginx and confd have confd update the nginx config and restart nginx whenever you add/remove app servers. Let’s say you have an etcd server that holds the IP addresses of your backend app servers. When that list changes confd can get a notification and write out a new nginx config and send a HUP signal to nginx to have nginx reload it’s config.

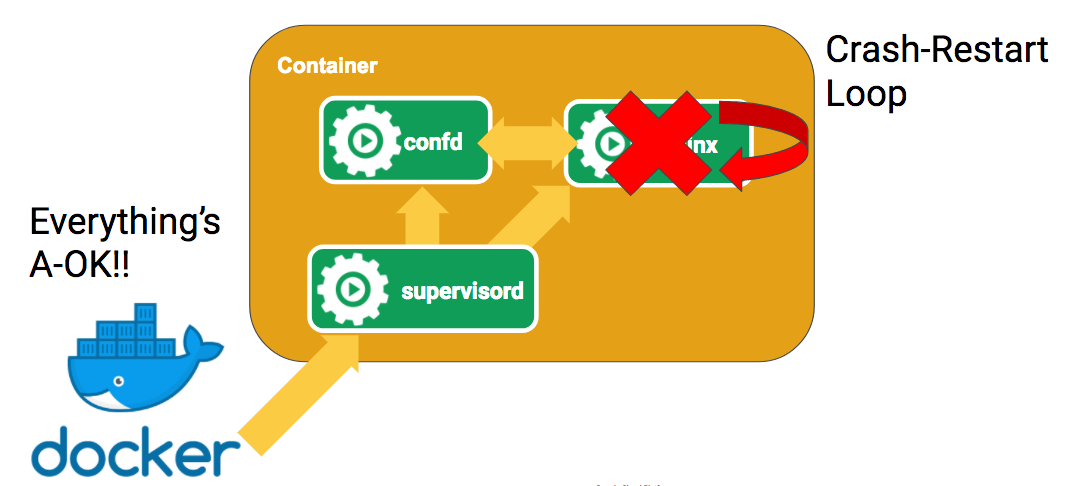

With Docker the way you would do this is put both nginx and confd in a single

container. Because Docker only has one entrypoint you need to keep both

processes running with something like supervisord. This is not ideal because you

need to run supervisord for every copy of nginx that you run. More importantly,

Docker only “knows” about supervisord because that’s the entrypoint. It doesn’t

have visibility into each process which means you and other tools can’t get that

info via the Docker API. Nginx might be crashing hard but Docker would have no

idea.

With pods Kubernetes manages each process and thus has insight into its state. That way it can provide info about that state to users via the API and can also provide services like restarting it when it crashes or automated logging.

Pods are Containers as an API

By being able to combine containers into Pods this way we can essentially create containers that can be added to Pods as an “API” that others can consume. This isn’t an API in the normal Web API sense, but rather an abstraction that other Pods can use.

For instance, take our nginx + confd example. In this example, confd doesn’t know anything about the nginx process. All it knows is that it needs to watch a value in etcd and send a HUP signal to a process or run a command. The app that it runs with doesn’t have to be nginx. It could be any kind of application. In this way, you could use the confd container image and configuration and swap it in with any number of different types of Pods. Pods where you can do that are usually called “sidecar containers” invoking the image of a sidecar on a motorcycle.

You can also think of other types of abstractions you could use. Service meshes like istio can be bolted on as sidecars and provide service routing, telemetry, policy enforcement without ever having to change the main application.

You can also use multiple sidecars. There’s nothing stopping you from using both the confd sidecar and istio sidecar at the same time. Applications can be combined in this way to build much more complex and reliable systems while keeping each individual app relatively simple.

Hopefully that’s given you a good idea of what Pods are and why they will be an

essential part of deploying containers in the future. If you are interested in

learning more about Kubernetes check out the Kubernetes

Slack. That’s where the best Kubernetes developers

get together to discuss all things Kubernetes. Check out the #kubernetes-users

channel for general discussion on all things Kubernetes.